Fast fashion clothes – we’ve all probably bought them at some point in our lives, unaware of the ramifications of their low price and low quality.

However, with each record-breaking heatwave and flood coming at us thick and fast, we are learning more and more about what is endangering our life on the only planet we have. And lo and behold – fast fashion is one of the reasons people on the shore would have to sell their houses to Aquaman.

But how does it do it? How does fast fashion slowly drag humanity into a cesspool of human rights abuses and climate catastrophe? Below are some snippets of facts that show its adverse effect on the world.

Key takeaways

- 1. Due to its business model, fast fashion is the main contributor to textile waste.

- 2. Up to 500,000 tonnes of textile-based microplastics enter the seas and oceans each year (again, fast fashion is the most responsible here, as their production costs must be rock bottom and synthetic materials sit alone at that rock bottom).

- 3. Over 13 million people working in the fashion industry are victims of modern slavery (fast fashion brands are the main drivers of this exploitative strategy)

- 4. Fast fashion takes the biggest chunk of the 2-8% CO2 emissions attributed to the textile industry

Now that we’ve made these bold claims, let’s not be lazy populist reactionaries about them and actually use facts to prove them. The first thing to do is find out how it all started.

History of fast fashion – the birth of a monster

*If you don’t care for history lessons, skip the whole bit and jump straight into the textile waste section.

The term fast fashion is relatively new – in the 1990s, New York Times coined the term to describe Zara’s retail strategy at the time. The strategy was based on translating the catwalk trends into ready-to-wear garments as quickly as possible. That meant that new styles were entering Zara’s retail stores every week, something no brand had done before.

However, the concept of clothing in a historical sense shows us that seeds of fast fashion were planted well before the 1990s. You could trace its predecessor to as early as 1830.

The emergence of ready-to-wear clothing

Before the invention of the sewing machine in 1830, to follow trends and have a wardrobe full of clothing, you’d have to be upper class. Going to a tailor was expensive since your only option was to get a made-to-measure garment.

The sewing machine flipped the script – its speed allowed for mass production and gave birth to the concept of ready-to-wear clothing. These were clothes made in standardized sizes, which allowed for a much lower price. Suddenly, the middle class and even the lower class could afford to be fashionable.

And guess what came with mass production? The good old labour rights and workplace safety violations, of course – staples of the fashion industry then, now, and tomorrow. And back in the day, it often happened in the developed world, even in Manhattan. Just like in our example below.

The Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire

Embed from Getty Images

March 25, 1911, saw the deadliest industrial disaster in New York City to date. One hundred and forty-six people died in a fire, out of which 123 girls and women and 23 men. The fire happened at a clothing factory owned by two controversial businessmen, who before this tragic event, had four accounts of suspicious fires in the buildings they ran their business at. To make matters worse, the factory was located on the 8th, 9th and 10th floor of the now Brown Building so the people had little chance of survival.

Did we say little? We meant almost no chance. Here’s why.

Being that it was the early 20th century when worker unions still had power, the two businessmen fought tooth and nail to stop their underpaid and often underage workers from unionizing.

One of the methods was to lock fire exits so that the union organizers couldn’t access the building. Another motive for locking the fire exits was to put additional pressure on the workers by restricting their movement.

In the epilogue of this sad event, controversial businessmen banked around $60k from insurance and didn’t serve even a millisecond of jail time, even though that was the fifth suspicious fire at a business they ran.

But that’s already too much politics for today. Let’s see how the seed of fast fashion turned into a sprout.

Growing need for more fashion in the post-WW2 era

Before the 60s and 70s, you’d add items to your wardrobe four times a year at best. However, with the post-war economic growth worldwide, people’s ability to spend grew and the fashion industry saw an opportunity. Instead of serving four seasonal styles a year, brands started dishing out more designs than ever before as there was more demand. This expansion went to crazy lengths that brought to life a curious fad called paper fashion.

Paper fashion?

In the 1960s, in the cradle of mindless consumerism – the USA, an intriguing fad reared its ugly head – disposable paper dresses.

You read it right. Paper. Dresses.

Embed from Getty Images

Scott Paper Company started the disposable fashion fad as a marketing trick to sell more paper goods. However, it went all too well, and they pulled the plug on the project once they were at the crossroads of branching out to garment manufacturing or sticking to what they know best – paper.

Regardless of this fad’s destiny, fashion kept accelerating in the coming decades. Also, paper dresses have set the stage for what is today’s fast fashion motto – wear it once and chuck it.

70s, 80s, and 90s: the rise of overseas manufacturers

The 70s marked the emergence of big textile mills in Asia and Central America. Clothing brands realized this on time and started the transition slowly. It wouldn’t be until the 90s that most brands would switch to an overseas manufacturing model.

With labour and raw material costs at an all-time low, clothing brands could afford to invest more in rewiring their consumers’ minds into even more mindless consumption. That mindlessness now means that an average person in the developed world wears a piece of clothing up to seven times before dopamine wears out, and they need another fix of fast fashion. A survey conducted by Barnardo’s in 2015 backs this up.

We now spend as much if not more on clothing but we litter the planet hundreds of times more, all thanks to fast fashion. Let’s get down to brass tacks of just how much it litters the planet.

Fast fashion and textile waste

To get all facts-don’t-care-about-your-feelingsy about fast fashion and textile waste, we present you the numbers from the research by the United States Environmental Protection Agency.

In 2018 in the US alone, there was a total of 17030 million tons of textile waste. Out of that total, 11300 million tonnes were landfilled, and 3220 million tonnes were incinerated. Compare it with the data from the 90s, when fast fashion started its exponential growth, that’s three times more. And it didn’t stop growing since 2018.

Now, not all of this belongs to fast fashion. But since fast fashion is the most productive branch of the fashion industry, a solid chunk of those emissions belongs to it. At least 20% or 2260 million tonnes of landfilled textile waste and 644 million tonnes of incinerated textile (which is burnt plastic for the most part). All this in a single year.

Let that sink in.

Microplastics and fast fashion – a sea full of particles

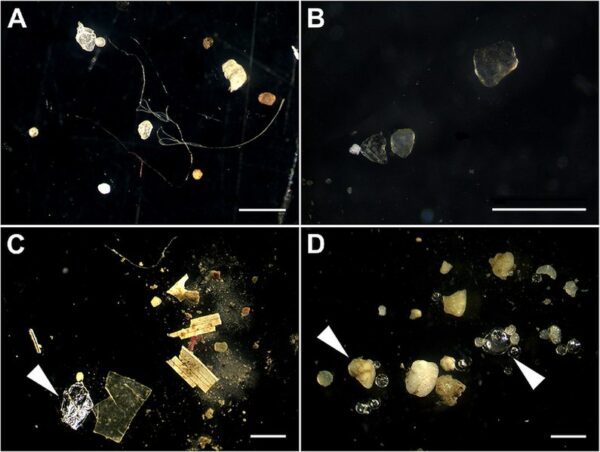

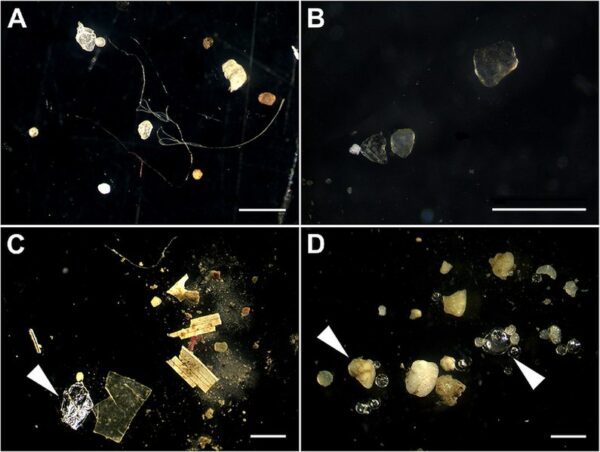

Microplastics in sediment from the rivers Elbe, Moser, Neckar, and Rhine.

Microplastics in sediment from the rivers Elbe, Moser, Neckar, and Rhine.

According to the European Environment Agency, ocean floors are home to over 14 million tonnes of microplastics. That number will only keep growing as every year, half a million tonnes of microplastics find their way into our rivers, lakes, seas and oceans.

Since most textile microplastics end up in a body of water after the first wash, you can deduce that most came from fast fashion items. Why? Because low-quality clothes pill the most. And what are fast fashion clothes known for? You guessed it – low quality.

Fast fashion in your blood? Yes.

We’re not talking figuratively here, we mean it literally. Environment International published a research paper that showed that 77% of its study participants had microplastics in their blood. Most of all polymers found was PET (50%), which is the most present polymer in polyester fibres, the bread and butter of fast fashion.

Researchers are still assessing the extent of the adverse effects of this to human health, but the signs are worrying as they should be. It’s plastics in our blood.

If you think you were dealt a bad hand as an active or passive consumer of fast fashion, wait until you learn how bad it is for the people making it.

You think slavery has ended? Think again.

Slavery is alive and well, and its permanent address is the textile industry, more precisely, the factories that make fast fashion.

To double-check this fact, all you need to know is simple math. A simple cotton t-shirt from a fast fashion brand costs around €8. A simple cotton t-shirt from a sustainable brand costs around €40.

Guess which brand can’t afford to respect labour laws and international humanitarian laws if it is to make a profit? Mhmm, the fast fashion brand.

That doesn’t absolve the sustainable brand in the slightest. If it wants, it too can break the laws and get away with it. Otherwise, we wouldn’t be in a situation where some of the poorest people in the world work in the textile industry.

Let’s see how this pans out in real life.

What fast fashion factories do to stay afloat

In the world we live in today, one thing holier than God almighty is profit. With that in mind, both the brand and the factory owner MUST make a lot of money. And if a brand owner that sells a t-shirt for €8 is to afford that new private island, he must bank at least €6 from it.

Then we have the factory owner that simply must buy that new Mercedes G-class SUV. He has a problem, though. He must settle for a €2 price for the cotton t-shirt. So how can he afford that SUV and charge just €2 for a tee?

Simple, he’ll steal from his workers. He and the brand owner make a deal with the government to turn a blind eye while he severely overworks and underpays his slav.. , ahem, workers, defunds workplace safety, and hires children.

And voilá, he’s got himself a great new ride while the brand owner is on his way to buy his next summer vacation destination.

Modern slavery stats

According to the 2018 study by the Global Slavery Index, 40.3 million people were victims of modern slavery, out of which 71% were women. By calculating the revenue of the top 5 items at risk of being made in modern-slavery conditions, almost a third of these people are prisoners of the fast fashion industry. That looks quite bad, right? If only humanity would have done something about it.

Well, it did. It doubled down. Walk Free, an international human rights group estimated that in 2021, there were 49.6 million people in modern slavery. The difference between 2018 and 2021 is over 9 million, which is equivalent to the population of London…

Now let’s see how fast fashion slowly tightens the grip on all our throats, not just the global south’s.

CO2 is the language of fast fashion

According to the McKinsey&Co and Global Fashion Agenda (2020) Fashion on Climate report, the fashion industry contributed 2-8% to the total annual global carbon emissions. Since fast fashion must cut corners everywhere to remain cheap, it is responsible for the vast majority of that 2 – 8 %.

Accessories to the crime

Fast fashion couldn’t do all these terrible crimes alone, it had massive help from corrupt and/or complacent governments.

Law and disorder

Many countries in the world have pretty decent labour laws. A vast majority do. However, not many apply them. In the countries where the most textile manufacturing happens, lawmakers often don’t enforce them at all and child labour, forced labour and a myriad of other human rights breaches are rife.

If it weren’t like that, you wouldn’t be reading this depressing article.

Conclusion

Congratulations, you made it to the end and now have a choice of these four emotions – anxiety, guilt, anger, and despair. You can combine them if you’d like.

Because fast fashion is here to stay, and no matter what we as individuals do to stop it from entering our water streams and bloodstreams, it will only grow stronger.

If things are really to change, there has got to be a worldwide, systematic effort to regulate or even stop fast fashion from existing, let alone growing.

And that, dear friends, will never happen because, in a world where growth is imperative, there’s no interest in regulating a money-making industry, regardless of how harmful for the finite planet it is.

So in a desperate and eventually unsuccessful effort to end on a moderately high note, we’ll quote Fred Astaire – “If you’re gonna go down, go down swinging!”

FAQ

- What are the 3 problems with fast fashion?

- What is the biggest problem with fast fashion?

- What is the most effective solution for fast fashion?

- What are other alternatives to reduce the impact of fast fashion?

- What are the negative social impacts of fast fashion?

- What’s the opposite of fast fashion?

What are the 3 problems with fast fashion?

The three problems with fast fashion are:

- Human rights abuses

- Destruction of the planet through textile waste and microplastics

- Allowing for the mindless consumerism mindset to flourish

Human rights abuses are something no fast fashion brand can do without – it’s a foundation of the profitability of such a business. The only difference between fast fashion brands is the extent of such abuses. Because for a product to be that cheap, making it from low-quality and often toxic materials isn’t enough. It must be manufactured in unlawful circumstances, where workers aren’t compensated fairly for their work.

Because fast fashion items are the ones that end up in a landfill after their users have worn them up to seven times, they litter the planet the most. Cheap clothes are mostly made from bad polyester fabrics that pill a lot. This is how fast fashion contributes to the growing problem of microplastics.

Fast fashion brands are mostly responsible for influencing their customers into buying clothes not out of necessity but out of boredom. Fast fashion is the main driver behind increased compulsive buying disorder of customers in western economies.

What is the biggest problem with fast fashion?

The biggest problem with fast fashion is that it is one of the main contributors to the growing issue of modern slavery. There are almost 50 million people trapped in modern slavery and a substantial percentage of that 50 million belongs to fast fashion.

What is the most effective solution for fast fashion?

Enforceable legislation would be the most effective way but is the least possible one. Countries that are home to most factories that commit crimes against humanity should enforce harsh penalties for such crimes. At this point in time, they don’t and it isn’t likely that they would in the foreseeable future.

Here’s how it would work. Once a factory can’t break labour laws and human rights laws, it wouldn’t be able to charge fast fashion brands miserably low manufacturing prices. As soon as that happens, the reason for such a brand’s existence perishes.

What are other alternatives to reduce the impact of fast fashion?

The alternatives would be things we as individuals can do and they are:

- Getting in touch with organizations like Clean Clothes Campaign and helping their campaigns in any way we can

- Informing the closest ones about the adverse effects of fast fashion

- Thrift and second-hand shopping

- Repairing and renting clothes

- Voting for ecologically conscious political options with a proven track record in the field (far-fetched, we know)

What are the negative social impacts of fast fashion?

Negative social impacts reflect in the following burning humanitarian issues in the countries where fast fashion manufacturing happens:

- Child labour

- Perseverance of modern slavery

- Perseverance of extreme poverty

All three issues are highly consistent in a vast majority of fast fashion clothing factories. Because profit for the brand and profit for the factory owners remains intact, the only variable left to suffer are the workers and they do suffer the most in this business model as proven by countless studies, some of which are mentioned in this blog post.

What’s the opposite of fast fashion?

Common sense. Common sense is the opposite of fast fashion.

Fast fashion’s only purpose for existing is to exploit the workforce and manipulate the consumer for a profit. Don’t get ensnared in its web of neural manipulation that cleverly hides all sorts of unlawful and amoral behaviours.

However, its more tangible alternative is slow fashion – a concept of buying clothes strictly out of necessity and with the idea of wearing them for the longest time possible. It includes the following:

- Buying new high-quality clothes made in ecologically and ethically sound circumstances

- If buying such clothes isn’t financially viable, buying at thrift stores and second-hand stores

- Repairing and renting clothes

Request a quote from us

To get the best possible price and lead time estimate, please include the number of designs and pieces per design, fabric choice, sizes, and printing options.